28 Bones Of The Skull

The emblem of Skull and Bones | |

| Germination | 1832 (1832) |

|---|---|

| Type | Secret guild |

| Headquarters | Yale University |

| Location |

|

| Region served | United States |

| Parent organization | Russell Trust Association |

Skull and Bones, also known as The Club, Order 322 or The Brotherhood of Decease, is an undergraduate senior secret student society at Yale Academy in New Haven, Connecticut. The oldest senior course social club at the academy, Skull and Bones has become a cultural establishment known for its powerful alumni and various conspiracy theories. Information technology is one of the "Big Three" societies at Yale, the other ii being Scroll and Cardinal and Wolf's Head.[1]

The society's alumni organization, the Russell Trust Association, owns the organization's real estate and oversees the membership. The society is known informally as "Basic," and members are known equally "Bonesmen," "Members of The Order" or "Initiated to The Order."[ii]

History [edit]

Skull and Bones was founded in 1832 after a dispute among Yale debating societies Linonia, Brothers in Unity, and the Calliopean Society over that season's Phi Beta Kappa awards. William Huntington Russell and Alphonso Taft co-founded "the Order of the Skull and Bones".[3] [4] The first senior members included Russell, Taft, and 12 other members.[five] Alternative names for Skull and Bones are The Social club, Order 322 and The Alliance of Decease.[six]

The social club'southward avails are managed by its alumni organization, the Russell Trust Association, incorporated in 1856 and named subsequently the Bones' co-founder.[3] The association was founded by Russell and Daniel Coit Gilman, a Skull and Bones member.

The outset extended clarification of Skull and Bones, published in 1871 by Lyman Bagg in his book 4 Years at Yale, noted that "the mystery now attending its existence forms the i great enigma which college gossip never tires of discussing."[7] [8] Brooks Mather Kelley attributed the interest in Yale senior societies to the fact that underclassmen members of then freshman, sophomore, and inferior course societies returned to campus the post-obit years and could share information about guild rituals, while graduating seniors were, with their knowledge of such, at to the lowest degree a step removed from campus life.[9]

Skull and Bones selects new members among students every spring as part of Yale University's "Tap Day", and has washed so since 1879. Since the lodge's inclusion of women in the early on 1990s, Skull and Bones selects fifteen men and women of the junior course to join the society. Skull and Bones "taps" those that it views every bit campus leaders and other notable figures for its membership.

The number "322" appears in Skull and Bones' insignia and is widely reported to be meaning as the year of Greek orator Demosthenes' death.[10] [11] [5] A alphabetic character between early society members in Yale's archives[12] suggests that 322 is a reference to the twelvemonth 322 BCE and that members measure dates from this twelvemonth instead of from the common era. In 322 BC, the Lamian State of war ended with the expiry of Demosthenes and Athenians were made to dissolve their regime and establish a plutocratic organisation in its stead, whereby only those possessing two,000 drachmas or more could remain citizens. Documents in the Tomb have purportedly been found dated to "Anno-Demostheni."[13] Members measure time of day according to a clock v minutes out of sync with normal time, the latter is called "barbarian time."

Ane fable is that the numbers in the society's emblem ("322") correspond "founded in '32, 2d corps", referring to a outset Corps in an unknown German academy.[14] [xv]

Facilities [edit]

Tomb [edit]

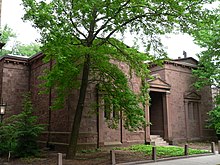

The Skull and Bones Hall is otherwise known as the "Tomb".

The tomb before the improver of a second fly

The building was built in three phases: the first wing was congenital in 1856, the second fly in 1903, and Davis-designed Neo-Gothic towers were added to the rear garden in 1912. The front and side facades are of Portland brownstone in an Egypto-Doric style. The 1912 tower additions created a small enclosed courtyard in the rear of the edifice, designed by Evarts Tracy and Edgerton Swartwout of Tracy and Swartwout, New York.[16] Evarts Tracy was an 1890 Bonesman, and his paternal grandmother, Martha Sherman Evarts, and maternal grandmother, Mary Evarts, were the sisters of William Maxwell Evarts, an 1837 Bonesman.

A 2009 view of the tomb from across High Street

The architect was maybe Alexander Jackson Davis or Henry Austin. Architectural historian Patrick Pinnell includes an in-depth discussion of the dispute over the identity of the original builder in his 1999 Yale campus history. Pinnell speculates that the re-employ of the Davis towers in 1911 suggests Davis's role in the original building and, conversely, Austin was responsible for the architecturally similar brownstone Egyptian Revival Grove Street Cemetery gates, built in 1845. Pinnell too discusses the Tomb's esthetic place in relation to its neighbors, including the Yale University Art Gallery.[16] In the late 1990s, New Hampshire landscape architects Saucier and Flynn designed the wrought fe fence that surrounds a portion of the complex.[17]

Deer Isle [edit]

The society owns and manages Deer Island, an island retreat on the St. Lawrence River ( 44°21′33″N 75°54′34″W / 44.359063°N 75.909345°Due west / 44.359063; -75.909345 (Location of New Skull & Bones Club Lodge on Deer Island) ). Alexandra Robbins, author of a book on Yale cloak-and-dagger societies, wrote:

The forty-acre retreat is intended to give Bonesmen an opportunity to "assemble and rekindle old friendships." A century ago the island sported tennis courts and its softball fields were surrounded past rhubarb plants and gooseberry bushes. Catboats waited on the lake. Stewards catered elegant meals. But although each new Skull and Bones member still visits Deer Island, the place leaves something to be desired. "Now it is just a bunch of burned-out rock buildings," a patriarch sighs. "It'due south basically ruins." Another Bonesman says that to call the isle "rustic" would exist to glorify information technology. "It's a dump, but information technology's beautiful."

Bonesmen [edit]

Yearbook listing of Skull and Basic membership for 1920. The 1920 delegation included co-founders of Fourth dimension magazine, Briton Hadden and Henry Luce.

Skull and Basic'south membership developed a reputation in association with the "power aristocracy".[xviii] Regarding the qualifications for membership, Lanny Davis wrote in the 1968 Yale yearbook:

If the society had a good twelvemonth, this is what the "platonic" grouping will consist of: a football captain; a Chairman of the Yale Daily News; a conspicuous radical; a Whiffenpoof; a swimming captain; a notorious drunkard with a 94 boilerplate; a film-maker; a political columnist; a religious group leader; a Chairman of the Lit; a greenhorn; a ladies' man with two motorcycles; an ex-service human; a negro, if in that location are enough to go around; a guy nobody else in the group had heard of, ever...

Like other Yale senior societies, Skull and Bones membership was well-nigh exclusively limited to white Protestant males for much of its history. While Yale itself had exclusionary policies directed at particular indigenous and religious groups, the senior societies were even more exclusionary.[19] [twenty] While some Catholics were able to join such groups, Jews were more than frequently not.[20] Some of these excluded groups eventually entered Skull and Bones by means of sports, through the society's practice of borer standout athletes. Star football players tapped for Skull and Bones included the outset Jewish actor (Al Hessberg, form of 1938) and African-American player (Levi Jackson, course of 1950, who turned down the invitation for the Berzelius Gild).[19]

Yale became coeducational in 1969, prompting some other secret societies such as St. Anthony Hall to transition to co-ed membership, yet Skull and Bones remained fully male until 1992. The Bones class of 1971's try to tap women for membership was opposed past Basic alumni, who dubbed them the "bad club" and quashed their endeavour. "The issue", as information technology came to be chosen by Bonesmen, was debated for decades.[21] The course of 1991 tapped seven female members for membership in the adjacent year's course, causing conflict with the alumni clan.[22] The trust inverse the locks on the Tomb and the Bonesmen instead met in the Manuscript Society building.[22] A mail service-in vote by members decided 368–320 to permit women in the club, but a grouping of alumni led by William F. Buckley obtained a temporary restraining club to block the motility, arguing that a formal modify in bylaws was needed.[22] [23] Other alumni, such every bit John Kerry and R. Inslee Clark, Jr., spoke out in favor of admitting women. The dispute was highlighted on an editorial folio of The New York Times.[22] [24] A 2nd alumni vote, in Oct 1991, agreed to accept the Class of 1992, and the lawsuit was dropped.[22] [10]

Members are assigned nicknames (e.one thousand., "Long Devil", the tallest fellow member; "Boaz", a varsity football game captain; or "Sherrife" prince of future). Many of the chosen names are drawn from literature (e.thou., "Hamlet", "Uncle Remus") religion, and myth. The banker Lewis Lapham passed on his nickname, "Sancho Panza", to the political adviser Tex McCrary. Averell Harriman was "Thor", Henry Luce was "Baal", McGeorge Bundy was "Odin", and George H. W. Bush was "Magog".[11]

Judith Ann Schiff, Chief Enquiry Archivist at the Yale Academy Library, has written: "The names of its members weren't kept secret—that was an innovation of the 1970s—but its meetings and practices were."[25] While resourceful researchers could gather member data from these original sources, in 1985, Charlotte Thomson Iserbyt provided Antony C. Sutton with rosters and records that had belonged to her father, a member of the system. This membership information was kept privately for over 15years, as Sutton feared that the photocopied pages could somehow identify the member who leaked it. He wrote a book on the grouping, America'southward Hush-hush Institution: An Introduction to the Lodge of Skull and Bones. The information was finally reformatted every bit an appendix in the book Fleshing out Skull and Bones, a compilation edited by Kris Millegan and published in 2003.

Among prominent alumni are former president and Chief Justice William Howard Taft (a founder's son); former presidents and begetter and son George H. W. Bush and George W. Bush; Chauncey Depew, president of the New York Central Railroad System, and a United States Senator from New York; Juan Terry Trippe, Founder & CEO, Pan American World Airways (Pan Am); Joseph Gibson Hoyt, the first chancellor of Washington Academy in St. Louis; Supreme Court Justices Morrison R. Waite and Potter Stewart;[26] James Jesus Angleton, "mother of the Central Intelligence Bureau"; Henry Stimson, U.S. Secretary of State of war (1940–1945); Robert A. Lovett, U.South. Secretary of Defense (1951–1953); William B. Washburn, Governor of Massachusetts; and Henry Luce, founder and publisher of Time, Life, Fortune, and Sports Illustrated magazines.[ citation needed ]

John Kerry, former U.S. Secretary of State and former U.Southward. Senator; Stephen A. Schwarzman, founder of Blackstone Group; Austan Goolsbee,[27] Chairman of Barack Obama'south Quango of Economic Advisers; Harold Stanley, co-founder of Morgan Stanley; and Frederick West. Smith, founder of FedEx, are all reported to exist members.

In the 2004 U.South. Presidential ballot, both the Autonomous and Republican nominees were alumni. George W. Bush-league wrote in his autobiography, "[In my] senior year I joined Skull and Bones, a secret gild; and so secret, I can't say anything more."[28] When asked what information technology meant that he and Bush-league were both Bonesmen, former presidential candidate John Kerry said, "Not much, because it's a secret."[29] [30] Tim Russert on Meet The Press asked both President Bush and John Kerry about their memberships to Skull and Bones, to which the president replied, "Information technology's then secret we can't talk virtually it." Kerry replied, "Yous trying to get rid of me here?"[31] [32]

Crooking [edit]

Skull and Bones has a reputation for stealing keepsakes from other Yale societies or from campus buildings; guild members reportedly telephone call the practice "crooking" and strive to outdo each other'due south "crooks".[33]

The society has been accused of possessing the stolen skulls of Martin Van Buren, Geronimo, and Pancho Villa.[34] [35]

Conspiracy theories [edit]

The grouping Skull and Basic is featured in books and movies which claim that the society plays a role in a global conspiracy for globe control.[36] There have been rumors that Skull and Basic is a branch of the Illuminati, having been founded by German university alumni following the order's suppression in their native land by Karl Theodor, Elector of Bavaria with the support of Frederick the Peachy of Prussia,[xiv] [ dubious ] or that Skull and Bones itself controls the CIA.[37]

References in fiction [edit]

- Skull and Bones has been satirized from fourth dimension to time in the Doonesbury comic strips by Garry Trudeau, Yale graduate and Roll and Key member. There are overt references, peculiarly in 1980 and December 1988, with reference to George H. West. Bush, and again when the club commencement admitted women.[38]

- The Skulls (2000) and The Skulls Two (2002) films are based on the conspiracy theories surrounding Skull and Bones.[39] A third film, The Skulls Three (2004), is based on the offset adult female to be "tapped" to bring together the society.

- In Baz Luhrmann's film version of F. Scott Fitzgerald's novel The Neat Gatsby, Nick Carraway calls Tom Buchanan Boaz. Tom in turn calls Nick Shakespeare. Nick has said earlier that he met Tom at Yale. It is thereby implied that they were in Skull and Bones together. In the novel, Yale is not explicitly mentioned (rather, they were at college in New Haven together) and it is only stated that they were in the same senior society.[xl]

- In The Good Shepherd (2006) the protagonist becomes a fellow member of Skull and Bones while studying at Yale.

- In The Simpsons flavour 28 episode "The Caper Chase," Mr. Burns visits the Skull and Bones society to meet with Bourbon Verlander about for-profit universities. In the episode "The Canine Wildcat" (flavour 8) afterward doing a secret handshake with a canis familiaris, Mr. Burns says: "I believe this dog was in Skull & Bones."

- In Family Guy episode, "No Chris Left Backside," when Chris Griffin is being bullied by the richer students at Morningwood Academy, Lois Griffin asks her father, Carter Pewterschmidt, to help Chris. And so Carter invites Chris to join Skull and Basic with the other students, who brainstorm to accept him. As office of his initiation, Carter and Chris adopt an orphan and lock him out of the car, which is filled with toys and a puppy, and then drive abroad when he'southward unable to get in. Chris though finds out how hard his family is working to pay for his school. At his initiation anniversary, Carter tells Chris that he must spend "Seven minutes in heaven" with their most senior fellow member, Herbert. Chris though feels uncomfortable almost joining and convinces Carter to assistance him get back into his old school.

- In American Dad! episode, "Bush-league Comes to Dinner," when President George West. Bush goes out drinking with Hayley, a drunken Bush dances and sings, "Let's all exercise the Skull and Basic!"

- In Season ane, Episode 33 of the 1966 Batman Television receiver serial, "Fine Finny Fiends" there is a gathering at Wayne Estate during which one guest points out a portrait of Bruce Wayne'south great-grandad wearing a Yale sweater. He asks if it is true that Bruce's ancestor was tapped for Skull and Bones, to which Aunt Harriet replies that he was not tapped for it, simply "he FOUNDED Skull and Bones!"[41]

See also [edit]

- List of Skull and Bones members

- Stewards Society

References [edit]

- ^ Jacobs, Peter (Oct 8, 2015). "Yale is revamping its hugger-mugger order organisation and so students don't feel left out". Business Insider . Retrieved April x, 2020.

- ^ Stevens, Albert C. (1907). Cyclopedia of Fraternities: A Compilation of Existing Authentic Information and the Results of Original Investigation as to the Origin, Derivation, Founders, Development, Aims, Emblems, Character, and Personnel of More than Six Hundred Cloak-and-dagger Societies in the United States. E. B. Care for and Visitor. p. 338. ISBN978-1169348677. OCLC 2570157.

- ^ a b "Change In Skull And Bones; Famous Yale Society Doubles Size of Its House – Addition a Indistinguishable of Old Edifice" (PDF). The New York Times. September 13, 1903. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ Niarchos, Nicolas; Zapana, Victor (December five, 2008). "Yale's clandestine social fabric". Yale Daily News . Retrieved November five, 2017.

- ^ a b Richards, David (May 2015). "The Origins of the Tomb". Yale Alumni Magazine . Retrieved November 5, 2017.

- ^ Blakely, Rhys (March two, 2013). "John Kerry and the 'Brotherhood of Decease' Yale secret society". The Times . Retrieved June 22, 2019.

- ^ Schiff, Judith Ann. "How the Surreptitious Societies Got That Way". Yale Alumni Mag (September/October 2004). Archived from the original on April iv, 2005. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ Bagg, Lyman Hotchkiss (1871). Four Years at Yale. New Haven, C.C. Chatfield & Co. ISBN978-1425569372. OCLC 2007757.

- ^ Yale: A History, Brooks Mather Kelley, (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Academy Press, Ltd.), 1974.

- ^ a b Hevesi, Dennis (October 26, 1991). "Shh! Yale's Skull and Bones Admits Women". New York Times . Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- ^ a b Robbins, Alexandra (May 2000). "George Due west., Knight of Eulogia". The Atlantic Monthly . Retrieved Nov 5, 2017.

- ^ "Alphabetic character from a member of Skull and Basic Gild to some other member". Yale Manuscripts & Archives Digital Images Database. Yale University Library. March 23, 1860. Retrieved November 5, 2017.

- ^ Stevens, Albert C. (1907). Cyclopedia of Fraternities: A Compilation of Existing Accurate Data and the Results of Original Investigation as to the Origin, Derivation, Founders, Evolution, Aims, Emblems, Character, and Personnel of More Than Six Hundred Underground Societies in the United States. E. B. Care for and Company. p. 340. ISBN978-1169348677. OCLC 2570157.

- ^ a b Robbins, Alexandra. Secrets of the Tomb: Skull and Basic, the Ivy League, and the Hidden Paths of Power. Back Bay Books, 2003.

- ^ "German postcard included in a Skull and Bones photo album originally owned by Chester Wolcott Lyman, BA 1882" [Photograph albums of the Skull and Bones Society]. Yale Academy Library Manuscripts and Archives. 1882.

- ^ a b Yale University 1999 Princeton Architectural Printing, ISBN ane-56898-167-8 Google Books

- ^ "Scull and Bones". Saucierflynn.com. Archived from the original on September 18, 2007.

- ^ Leung, Rebecca (June 13, 2004). "Skull And Basic: Secret Yale Guild Includes America'due south Power Aristocracy". CBS News . Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- ^ a b Oren, Dan A. (1985). Joining the Gild: A History of Jews and Yale . New Haven: Yale University Printing. pp. 87–88. ISBN0-300-03330-3.

- ^ a b Karabel, Jerome (2005). The Chosen: The Hidden History of Admission and Exclusion at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton . Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 53–36.

- ^ Robbins, pp. 152–159

- ^ a b c d e Andrew Cedotal, Rattling those dry bones, Yale Daily News, April 18, 2006.

- ^ "Yale Alumni Block Women in Surreptitious Guild". New York Times. September vi, 1991. Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- ^ Semple, Robert B. Jr. (April 18, 1991). "High Apex on High Street". New York Times . Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- ^ Yalealumnimagazine.com Archived April 4, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Barron, James (July 25, 1991). "Male Fortress Falls at Yale: Bonesmen to Admit Women". New York Times . Retrieved Feb 28, 2009.

- ^ Bray, Aaron (October 12, 2007). "Goolsbee '91 puts economics caste to use for Obama". Yale Daily News. Archived from the original on Oct three, 2012.

- ^ Bush, George West. (1999). A Charge to Proceed . William Morrow and Co. ISBN0-688-17441-8.

- ^ Oldenburg, Don (April 4, 2004). "Bush, Kerry Share Tippy-Top Secret". The Washington Mail. Archived from the original on August 12, 2018. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ Meet the PrintingGoogle Video

- ^ NBC News (Feb 13, 2004). "Transcript for Feb. 8th". msnbc.com . Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ NBC News (April 18, 2004). "Transcript for Apr 18". msnbc.com . Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Lassila;Branch (2006). "Whose skull and bones?" (PDF). Yale Alumni Magazine: xx–22.

{{cite periodical}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Greenburg, Zach O. (Jan 23, 2004). "Bones may take Pancho Villa skull". The Yale Herald. Archived from the original on Dec twenty, 2008. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ Citro, Joseph A. (2005). Weird New England (illustrated ed.). Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. pp. 270–71. ISBNi-4027-3330-five.

- ^ Stephey, MJ (Feb 23, 2009). "A Brief History of the Skull & Bones Society". Fourth dimension. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009.

- ^ Dempsey, Rachel (January eighteen, 2007). "Real Elis inspired fictional 'shepherd'". Yale Daily News. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved Apr 5, 2012.

- ^ Soper, Kerry (2008). Garry Trudeau: Doonesbury and the Aesthetics of Satire. University Printing of Mississippi. pp. 25, 42. ISBN978-1-934110-89-8.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. (July x, 2013) The Skulls Picture show Review & Film Summary (2000) | Roger Ebert. Rogerebert.suntimes.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-15.

- ^ "The Swell Gatsby". Publicbookshelf.com. Archived from the original on Apr 7, 2014.

- ^ Holy Eli, Batman!

Farther reading [edit]

- Hodapp, Christopher, and Alice Von Kannon (2008). Conspiracy Theories & Secret Societies For Dummies. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN 978-0470184080.

- Jarrett, William H. (2011). "Yale, Skull and Bones, and the Beginnings of Johns Hopkins". Baylor University Medical Centre Proceedings. Baylor University Medical Heart. 24 (1): 27–34. doi:10.1080/08998280.2011.11928679. PMC3012287. PMID 21307974.

- Klimczuk, Stephen, and Gerald Warner (2009). Hush-hush Places, Hidden Sanctuaries: Uncovering Mysterious Sites, Symbols, and Societies. New York and London: Sterling Publishing. ISBN 978-1402762079. pp. 212–232 ("Academy Cloak-and-dagger Societies and Dueling Corps").

- Robbins, Alexandra (2003). Secrets of the Tomb: Skull and Bones, the Ivy League, and the Hidden Paths of Power. Back Bay Books. ISBN 0316735612.

- Rosenbaum, Ron (Sep. 1977). "The Last Secrets of Skull and Bones." Esquire.

- Sutton, Antony C. (2003). America's Secret Institution: An Introduction to the Lodge of Skull & Basic. Walterville, OR: TrineDay, 2003. ISBN 0972020705.

- Sutton, Antony C., et al. (2003). Fleshing Out Skull & Basic Investigations Into America'south Most Powerful Clandestine Gild. TrineDay. ISBN 0972020721 (hardcover). ISBN 0975290606 (softcover).

External links [edit]

- Yale University archives of Skull and Bones

- A await inside Yale'south secret societies – and why they may no longer affair

28 Bones Of The Skull,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skull_and_Bones

Posted by: marchfaryinly.blogspot.com

0 Response to "28 Bones Of The Skull"

Post a Comment